Hand washing is perhaps the only protective measure that the entire scientific community accepts unquestionably to stop the spread of Covid-19, but also of any disease, since they spread mainly through droplets expelled by the person who has it and contact with surfaces that they have touched. Microbiologists began to realize this after 1860, when modern microbial theory began to develop, pioneered by John Snow, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch.

However, it was the Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister who, in 1867, promoted the idea of disinfecting hands and surgical instruments to stop infectious diseases, and despite the criticism he initially received, from the 1870s onwards doctors began to wash their hands thoroughly and systematically before each surgery.

And while today everyone (I hope) recognizes hand washing as one, perhaps the easiest, way to stay healthy, in the 1840s this thought cost a doctor his career. But let's start from the beginning.

Puerperal Fever: A Nightmare in 19th Century Europe

In the 1840s, Europe was facing a huge problem with a disease that has been identified since the time of Hippocrates but for many years we have forgotten its existence thanks to the progress of science: puerperal fever .

Because of this disease, many new mothers fell ill and died shortly after giving birth, even receiving the best medical care of the time.

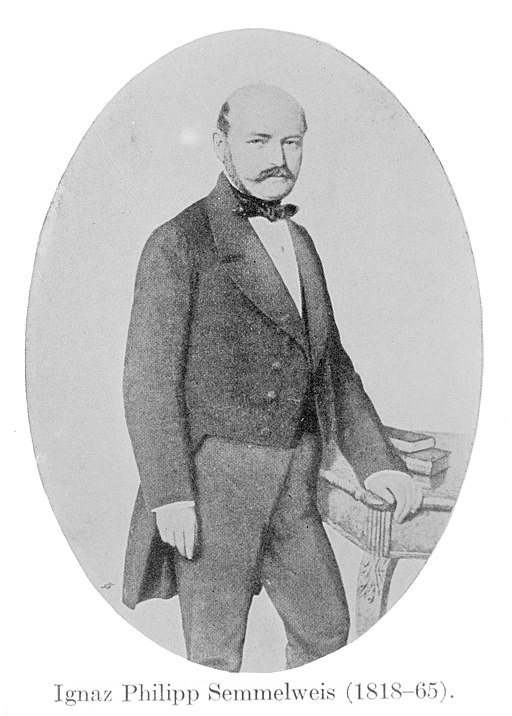

Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis was aware of the problem since he worked at the Vienna General Hospital in Austria, which had two separate maternity wards:

- The one staffed exclusively by doctors

- And the other one from midwives

Semmelweis was determined to locate the source of the evil and was astonished when he observed the following:

The mortality rate from puerperal fever was much lower when midwives delivered the babies, in contrast to women who, while under the care of doctors and medical students, and therefore in “better hands,” paradoxically died at twice the rate.

The first cases

Semmelweiss tested a number of hypotheses about the phenomenon. His first thought was whether a woman's body position during childbirth created the problem. He then studied whether a woman's awkwardness around male doctors caused the fever. He even went so far as to test whether priests who visited patients before their last breath scared the other mothers to death. In general, Semmelweis considered and evaluated every factor he could think of, but none of them were convincing, so he ruled them out.

The revelation

Semmelweis didn't stop looking for the difference between the two maternity hospitals until he found the culprit: the corpses .

Every morning at the hospital, doctors supervised and assisted students with autopsies as part of their medical training. In the afternoons, however, doctors and students worked in the maternity ward, either examining patients or performing deliveries. In contrast, midwives were limited exclusively to their duties in the maternity ward.

Remember, this was 1847, so germ theory was in its infancy, with little understanding of the microcosm as we understand it today. Since the word microbes hadn't yet been invented, Semmelweis assumed that they were "organic matter from decaying animals" that were transferred from dead bodies to the hands of doctors and then to new mothers.

And because at that time doctors did not wash their hands between operations and patient visits, any pathogens they came into contact with during the autopsy (and beyond) were transferred to the delivery room.

Vienna 1847: The landmark date for handwashing

In 1847, Semmelweis introduced mandatory handwashing for doctors and students working for him at the Vienna General Hospital, as well as for the medical instruments they used. He even went a step further, using a solution of calcium chloride instead of soap, because it completely removed the smell of the morgue from the doctors' hands. And just like that, the mortality rate in the hospital's maternity ward plummeted.

The reactions of the scientific community

If you think that Semmelweis was awarded and entered the pantheon of medical science with honors, then you are wrong.

When in the spring of 1850, Semmelweis took to the stage of the prestigious Vienna Medical Association and presented his theory and its results, the medical community rejected him outright, mocking both his scientific credentials and his logic. And while the outrageous reduction in mortality rates in the maternity wards of the Vienna Hospital was a fact, since after the imposition of hand hygiene, the rate fell from 18% to 1%, immediately after that the hospital abandoned the practice of mandatory hand washing .

Disappointed, he resigned from his position and continued his career in Pest, Hungary, where he also worked in a maternity hospital, establishing systematic hand and instrument washing there, drastically reducing the maternal mortality rate once again.

A few years later, in 1858 and 1860, he published articles on the beneficial properties of handwashing , and he also published a book in 1861. His book was condemned by almost the entire medical community, which proposed other, completely absurd, theories for the continued spread of puerperal fever. Unfortunately, Ignaz Semmelweis died in 1965 without even recognizing the successful saving of hundreds or even thousands of lives.

The vindication that took 2… or 100 years

In 1867, two years after his death, Joseph Lister (on whose work Louis Pasteur relied for the development of germ theory a few years later) and despite countless critics, confirmed and established the disinfection of hands and surgical instruments in medical care. Consequently, the international recognition of Semmelweis' previous work.

What if surgeons started washing their hands systematically in the 1870s?

The importance of daily handwashing became universal more than a century later, only in the 1980s when hand hygiene was incorporated into national guidelines in the United States and other first-world countries. At the same time, the Medical University of Budapest changed its name to Semmelweis University, thus honoring the pioneer of the antiseptic method and the optimization of healthcare through the cleanliness and washing of hands and medical instruments.