One of the most common and serious complications associated with catheters is urinary tract infections (UTIs). A urinary tract infection (UTI) is defined as catheter-associated (CAUTI) if a catheter was in place (even intermittently) within 7 days prior to the onset of the infection.

Although most often catheter-related urinary tract infections are asymptomatic, when a CAUTI becomes symptomatic, the consequences can range from mild to severe.

- fever,

- urethritis and

- cystitis

to serious as

- epididymitis,

- acute pyelonephritis,

- kidney scars,

- stone formation and

- bacteremia.

If left untreated, these infections can even lead to sepsis and death.

Since the risk of CAUTI increases with the duration of catheterization and patients are not subject to continuous clinical monitoring, these complicated infections usually recur and lead to long-term morbidity due to the presence of overlaps in the catheter-collection system. Thus, patients are at high risk of infection and are more likely to suffer the complications that can arise as a consequence of a catheter-related UTI and the associated biofilm ( Kohler-Ockmore and Feneley 1996 ; Stickler 2014 ).

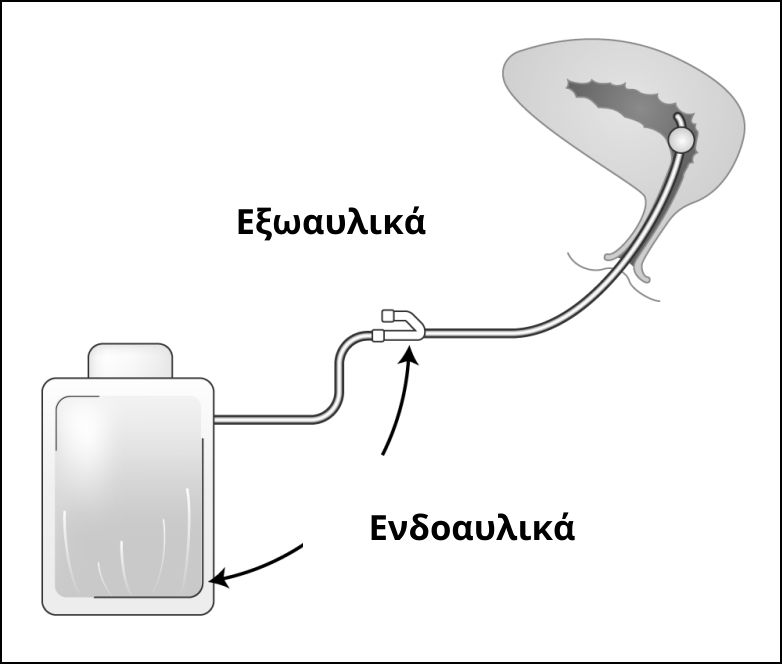

Extraluminal and intraluminal infections

The presence of an indwelling catheter is the most important risk factor for bacteriuria . Most bacteria that cause CAUTI gain access to the urinary tract either extraluminally or intraluminally.

Catheter-related urinary tract infections are common because indwelling catheters introduce microorganisms into the bladder and facilitate colonization by providing a surface for bacterial adhesion and causing mucosal irritation.

Internally or externally, microorganisms migrate from the catheter to the bladder within one to three days.

Generally speaking, there are three entry points for catheter-related bacteria:

- The urethral orifice , with the introduction of bacteria during catheter insertion.

- The catheter-ureter connecting part , especially when there are cracks.

- The drainage port of the urine collector .

These three areas are involved in urinary tract colonization and infections and usually combine to make it very difficult to prevent urinary tract infections in people with indwelling catheters that last longer than 2 weeks .

Extraluminal infections usually occur during catheter insertion , due to contamination from any source, however, they are also believed to be caused by microorganisms that ascend from the perineum along the surface of the catheter.

Fecal strains contaminate the perineum and urethral orifice and then ascend to the bladder along the external surface to cause bacteriuria, biofilm formation, and coatings that can gradually lead to catheter obstruction.

Catheter-related urinary tract infections are more likely to occur in women than in men due to the shorter female urethra and the close proximity of the urethra to the anus, resulting in bacteria having a shorter distance to travel.

Intraluminal infections occur with the ascendance of bacteria from an infected catheter, drainage tube, or urinary catheter .

Studies show that at least 66% of CAUTIs originate from extraluminal infection, while 34% are the result of the intraluminal route.

A prospective study of pathogenesis of catheter-associated urinary tract infections

Urinary tract infection from a catheter: Symptoms

Symptoms of indwelling catheter-related infection are often nonspecific. They are caused by the inflammatory response of the urinary tract epithelium to bacterial invasion and colonization.

However, the classic clinical manifestations of urinary tract infection

- pain

- Urinary urgency

- dysuria

- fever

- leukocytosis

are unusual even when bacteria or yeast are present .

A typical example is that often confusion or unexplained fever may be the only symptoms of a CAUTI in nursing homes.

At the same time, diagnosis in patients with spinal cord injury can be particularly difficult from history and physical examination due to the frequent lack of local symptoms. Often, the only symptoms are fever, sweating, abdominal discomfort, or increased muscle spasticity.

Bacteriuria

Bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) is common in most patients who have had an indwelling catheter in place for 2 to 10 days . There is a large number and variety of organisms in the periurethral area and its distal parts that may invade the bladder at the time of catheter insertion.

Other factors that increase the risk of bacteriuria include:

- Presence of residual urine due to inadequate bladder drainage.

- Ischemic damage to the bladder mucosa due to overdistension.

- Irritation from the presence of a catheter.

- Biofilm development on the intraluminal surface of the catheter.

Catheter-associated bacteriuria is usually asymptomatic and uncomplicated and is left untreated as it gradually resolves in an otherwise normal urinary tract after catheter removal. This is not the case for those who are forced to use an indwelling catheter for a long period of time .

Statistical studies reveal the scale of the problem

Once an indwelling catheter is placed, the daily probability of developing bacteriuria is 3 to 7% .

Strategies to Prevent Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update

Between 10% and 30% of patients undergoing short-term catheterization, i.e. 2 to 4 days , develop asymptomatic bacteriuria .

1em"> Over 90% of patients undergoing long-term catheterization develop bacteriuriaApproximately 80% of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections are related to urethral catheterization , while only 5 to 10% are related to other manipulations of the genitourinary system.

Prevention of bacteriuria

The presence of potentially pathogenic bacteria and the indwelling catheter predispose to the development of nosocomial urinary tract infections . Bacteria can enter the bladder during catheter insertion, during handling of the catheter or drainage system, around the catheter, and after its removal.

At least two basic principles should be used to prevent bacteriuria :

- Almost all systematic studies show that the use of a closed-circuit urinary catheter with an anti-reflux valve significantly reduces the rate of urinary tract infections .

- The indwelling catheter should be removed as soon as possible.

Hospital-acquired urinary tract infections associated with indwelling catheters

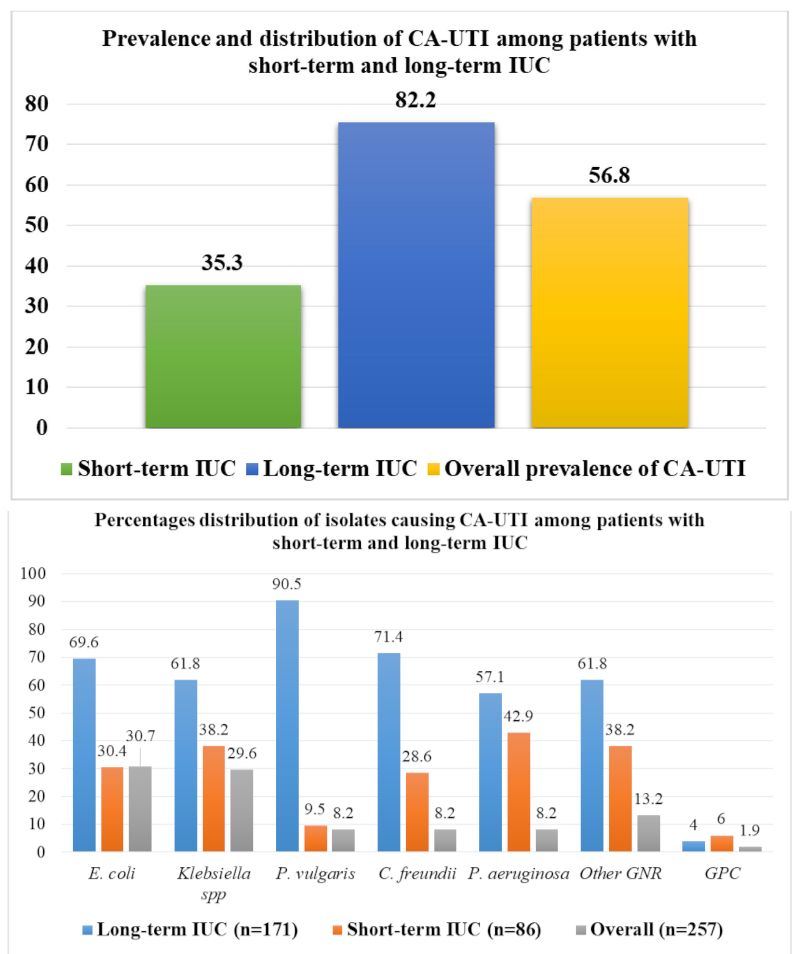

CAUTIs are the most common nosocomial infections in hospitals and nursing homes , accounting for more than 40% of all community-acquired infections. However, they are considered complicated urinary tract infections and are the most common complication associated with long-term catheter use .

Above: Prevalence & distribution of catheter-related urinary tract infections among patients with short-term and long-term use.

Bottom: Percentage distribution of organisms causing catheter-related urinary tract infections among patients with short-term and long-term use.

Urinary Tract Infections and Associated Factors among Patients with Indwelling Urinary Catheters Attending Bugando Medical Center a Tertiary Hospital in Northwestern Tanzania

Catheter-related urinary tract infections can occur at least twice a year in patients with long-term use because catheters are an ideal medium for bacterial growth because biofilms adhere to the many surfaces provided by the catheter-urine collection system .

Increased antibiotic use has led to an increase in antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans , two organisms frequently implicated in hospital-acquired infections associated with indwelling catheters.

Candidiasis is particularly common in individuals with prolonged urinary catheterization who are receiving broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobial agents.

Candida urinary tract infection: pathogenesis

Also a major problem in hospitals and long-term care facilities are infections with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) .

Most catheter-related urinary tract infections involve multiple organisms and resistant bacteria from biofilms associated with long-term catheter use such as:

- Enterobacteriaceae

- E. coli

- Klebsiella

- Enterobacter

- Proteus mirabilis

- Citrobacteria

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Enterococci

- Staphylococci

- Candida

Biofilm and indwelling catheters

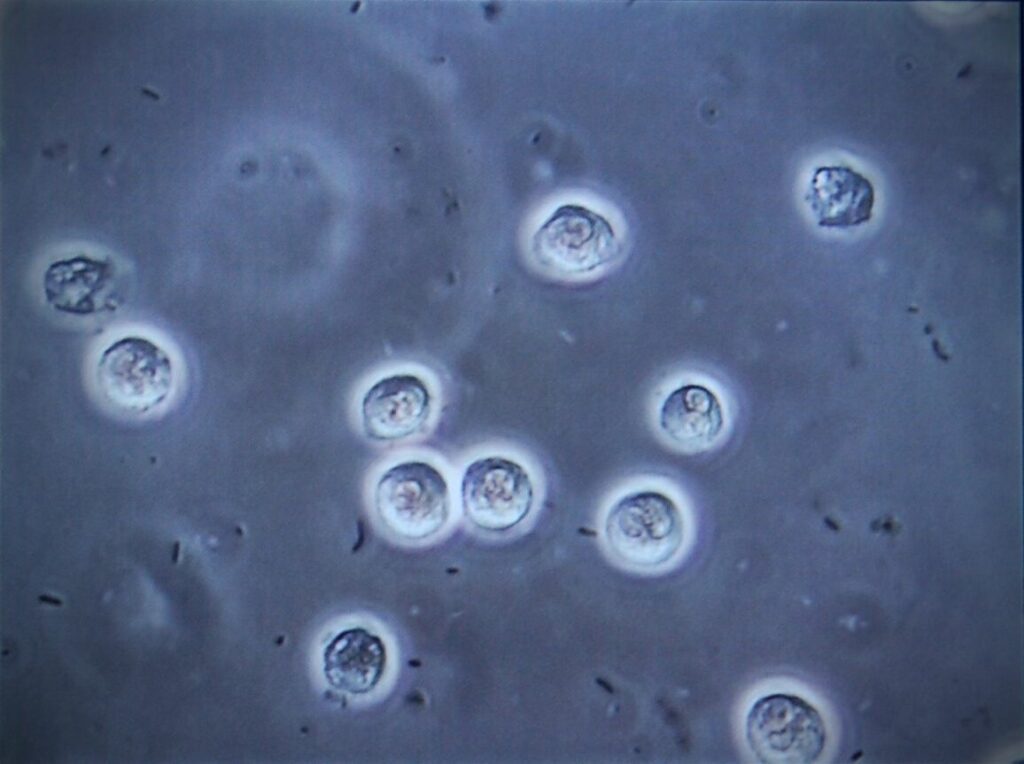

Biofilms usually begin to develop within the first 24 hours after catheter insertion, and in some cases rapidly become so thick that they completely occlude the catheter lumen. The presence of biofilms has important implications for antimicrobial resistance, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-related urinary tract infections.

A biofilm is a collection of microorganisms with altered phenotypes that colonize a surface, living or non-living, such as the outer surface of a trauma bed or a medical device.

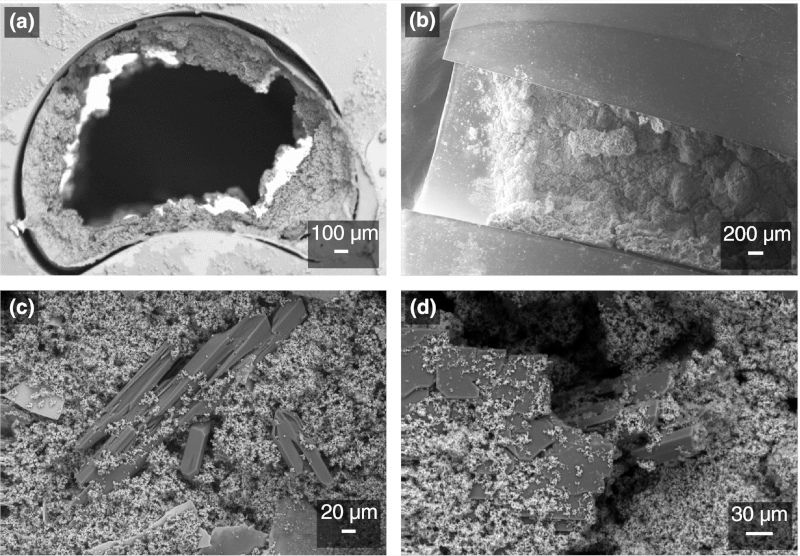

Proteus mirabilis crystalline biofilms. Examples of Proteus mirabilis crystalline biofilms formed on standard silicone Foley catheters, in in vitro models of the catheterized urinary tract.

Bacterial biofilm formation on indwelling urethral catheters

Urine contains a protein that adheres to and primes the surface of the catheter. Microorganisms bind to this protein layer and thus adhere to the surface. These bacteria are different from free-floating planktonic bacteria, i.e. bacteria that float in the urine.

Urinary catheter biofilms may initially consist of single organisms, but long-term exposure inevitably leads to multi-organism biofilms. Bacteria in biofilms have significant survival advantages over free-living microorganisms, as they are highly resistant to antibiotic treatment .

The relationship between biofilm and urinary tract infection is that biofilm provides a stable reservoir of microorganisms that, upon detachment, can infect the patient.

At the same time, biofilms cause further problems if bacteria (such as Proteus mirabilis) produce the enzyme urease which makes the urine alkaline (increased pH), causing the production of ammonium ions, followed by crystallization of calcium and magnesium phosphate within the urine. These crystals then become embedded in the biofilm, resulting in catheter blockage .

Cross-section of a silicone catheter removed from a patient after occlusion. Crystalline materials appear to completely occlude the catheter lumen.

Complicated Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections Due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis

Several characteristics of biofilms have important implications for the development of antimicrobial resistance in organisms that grow within them. Because the presence of biofilm inhibits antimicrobial activity, organisms within the biofilm cannot be eliminated by antimicrobial therapy alone. Just as in wounds, biofilm on catheters provides a protective environment for microorganisms that does not allow them to come into contact with antimicrobial agents. Biofilm also allows microbial adhesion to catheter surfaces in a manner that does not allow removal by gentle saline irrigation .

In contrast, a 0.02% polyhexanide solution is capable of reducing bacterial biofilm from catheters . Data show a reduction in the viability of viscous bacterial biofilms on a variety of commercially available urinary catheters made of silicone, latex-free silicone, hydrogel-coated silicone, and PVC (com/articles/10.1186/s12894-021-00826-3" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener"> Florian HH Brill, et al. 2021 ).